Note: 1/9 @ 8:30 a.m.

Course Information1

1 Acknowledgments: I thank Heather Shearer (Teaching Professor at UC Santa Cruz) for meeting with me and sharing her expertise with labor-based grading. I also thank Asao Inoue (Professor of Rhetoric and Composition at ASU) for his research and mentorship regarding contract grading. Now that AI tools such as ChatGPT are widely available, I believe it makes more sense than every to try ungrading.

Spring 2024, ENC 3266, Credit Hours: 3, Department of English

Class Meeting Days: N/A. This course is delivered asynchronously.

University Course Description

Students will be introduced to the idea of research as inquiry and as a knowledge-making enterprise that is used in the workplace to solve problems or answer questions. By exploring the research methods used in the PTC fields, students will develop an awareness of how professionals in the field of professional and technical communication develop an idea, plan a research project, go about gathering data (whatever “data” may be), perform analysis, and present their work.

USF Core Syllabus Policies

USF has a set of central policies related to student recording class sessions, academic integrity and grievances, student accessibility services, academic disruption, religious observances, academic continuity, food insecurity, and sexual harassment that apply to all courses at USF. Please be sure to review these online: “>USF Core Syllabus Guidelines <usf.edu/provost/faculty-success/resources-policies-forms/core-syllabus-policy-statements.aspx>

Instructor Information

Joseph M. Moxley, Professor of English

He/Him/His

College of Arts & Sciences

Office Hours

Tuesdays and Thursdays, 2-3 p.m. and by appointment. Please email me when you have questions: mox@usf.edu. I’ll typically respond pretty quickly. If you don’t hear from me within 24 hours, pls send me a 2nd email. I’m generally available via Teams throughout the workday, especially the afternoons. Don’t hesitate to reach out. I don’t mind jumping on a call. I’d much rather have you ask sooner rather than later. We can meet online through Teams, Zoom, or Google Meet. Let me know your preference.

Welcome

Dear Students,

Welcome to ENC 3266 – Research for PTC. Below is the course requirements and schedule.

Throughout the course, at least two times each week, please check

Spring 2024, ENC 3266, Credit Hours: 3, Department of English

Class Meeting Days: N/A. This course is delivered asynchronously.

Welcome

Dear Students,

Welcome to ENC 3266 – Research for PTC. Below is the course requirements and schedule.

Throughout the course, at least two times each week, please check Announcements @ Canvas. I make weekly and often biweeklyAnnouncements. For instance, for the class I may clarify a student question, or I may give some group feedback on an assignment. Please email me when you have questions. I’ll typically respond back in 24 hours. If you don’t hear from me within 24 hours, pleases send me a 2nd email. If I’m online when your message comes in, I’ll jump on a quick call with you, via Zoom, Teams, or Google Meet. We can schedule longer meetings, as necessary.

My AI Policy

I’m all for your using AI tools such as Chat GPT or Midjourney. I think moving forward, like it or not, we will be working a lot with AI to accelerate communication processes. However, I strongly encourage you to develop your own unique style, voice — and thoughts. At this point of time, it’s easy to recognize a prose style generated by AI: it tends to address content at the superficial level, it hallucinates, and it tends to follow a formulaic sentence and organizational structure. Remember, as well, that tools such as ChatGPT are founded on the greatest intellectual property theft of all time: The developers vacuumed the internet, swallowing all of that content whole. They didn’t care about U.S. copyright law or intellectual property rights — or the laws that protect a writer’s work in other countries. Instead, they dumped all of those words into a bucket — what corpus linguists call a corpus. Then they used statistical probability analysis to predict which letter or letters are likely to follow other letters. Then they used humans to train the dataset.

You should know that I can tell when work is based on AI and served up whole as if context doesn’t matter in clear communication. I can also determine, I believe, whether your prose has been worked though multiple iterations. Eventually, it may be impossible to discern AI prose from human prose. Presently, though, that’s not the case.

Currently, in higher education there is a great deal of conversation and debate about how professions and disciplines should respond to the usage of AI assisted writing for classroom assignments.

In my opinion, we are in a pickle: the conventions that have guided our society regarding intellectual property are shifting in response to the emergence of large language models. Professional organizations, journals, and book publishers are working on new methods for attributing sources generated from humans coauthority with AI. Lawyers and businesses and the government are wresting with how AI can be used for the benefit of humanity. We are at a revolutionary moment when it comes to language practices. People in school and workplaces are suddenly grappling with powerful AI-informed Digital Assistants, who are capable of setting their appointments and doing routine writing. All of this brings into question what the future is for writing and professional writers, and how if humans strop writing that may influence cognition and the ongoing conversations of humankind

Meanwhile, though, it’s also important to note that in school settings and work settings it is a violation of academic and/or professional integrity for you to submit work that has make up sources and evidence. Thus, if you experiment with AI, you must not simply “copy and paste.” Instead, you need to check every source and quotation — really every word. So, from my perspective, it’s fine for you to work with AI but whatever you turn in needs to be yours: it needs to reflect your voice, tone, voice, persona — and thinking.

Personal Pronouns

So that I may refer to you with the appropriate pronoun in Canvas, the University’s course LMS (learning management system), please set your preferences for your personal pronoun at Canvas > Settings. If you have a first name change request for Canvas, please email IDM-Help@usf.edu from your official USF email account. You do not need to provide personal details for the request. Tell USF the first name you want to show in Canvas. This will also change your name in the directory, but it will not change your email address.

How Can You Do Well in This Class?

- Show up.

- Show up every time we meet.

- Show up on time.

- Show up ready to participate enthusiastically in class activities and class discussions.

- Show up prepared (i.e., complete all assigned readings and assignments before class).

Best wishes for a productive semester.

Professor Moxley

Student Learning Outcomes

- Learn about the research methods employed by practitioners in PTC

- Question ways ideology and epistemology impinges on both interpretation and research methods

- Sharpen your information literacy perspectives and practices

- Learn how to manage research projects.

Course Delivery

This course is offered asynchronously by USF, which means it does not require real-time interactions either in person or online. Rather than convening at a specific time, this format allows you the flexibility to engage with course materials and complete assignments according to your own schedule. Below, you will find a detailed outline of the course assignments along with a schedule designed to guide you through these tasks in a timely and structured manner.

Required Course Tools – Writing Spaces

- Canvas (for grading purposes & Announcements)

- Each week, I will use Announcements @ Canvas to adjust the schedule, if necessary, clarify student questions, and give group feedback. I will ask you to upload some assignments to Canvas discussion forms and drop boxes.

- gDocs

- Zotero (for citations — unless you have another favorite app for citation management)

Required Texts

- GCF Global. Google Drive and Docs

This is a thorough, free guide to using gDocs. You’ll need this resource if you are unsure how to create and share gDocs - Web Accessibility Initiative. Images Tutorial

This is a free resource. Not sure how to caption images? Learn how to make your images more accessible. - Rewriting Work

- Syllabi Policies for AI Work

- We will study this corpus for our collaborative, class-wide project. Note this form is also available as a searchable spreadsheet

- Try This

This is the major course textbook for this course - Writing Commons

You can block the ads by adding Adblock Plus, a free Chrome extension. The ad blocker works great.

Recommended Resources

- USF Guidance for Ethical Generative AI Usage

- USF AI Resources & Tools

- Grading

Your grade will be based on your labor over the semester. This approach is called “labor-based contract grading.” Ideally, contract grading frees you up to try new things because you won’t be penalized for taking risks. In fact, I strongly (!!) encourage you to try new things and push yourself. Growth and strength result from struggle and working through confusion.

Grading Criteria

To earn an A in this course, you need to meet all of the requirements outlined above to earn a B grade AND you must work on a second project for this class that is being completed solely for this class. Choose from one of the following options. Or, if you have a better idea, tell me about it. I’d like for you to write a topic that you find interesting.

- Write in any nonfiction genre or media the equivalent of a 1000 to 1500 word article on any topic of your choice. This text should be written for a specific discourse community/magazine/journal. Even if at heart its an alphabetical text, it needs to be well designed. For instance, it should have a professional page design, be visual appealing, and include data visualizations such as infographics

- Develop a blog for a public audience. Spend the semester blogging and researching how to commercialize a blog. Research the topic you’d like to write about and the market niche. Identify leading blogs in that market. Each week write at least two 500 word posts on topics for your market/audience. Add necessary visualizations (at least one for each post).

- In the course plan below, you are scheduled to summarize and critique about five articles published in the PTC field. For this project, you would continue that work but do more of it. You’d read and summarize/critique two additional articles each week from the list of PTC articles below.

- Write a 500-word book review of a book that explores research methods in professional and technical communication. Choose from the following recently published OER books or email me if you wish to write a book review for an alternative book related to the topic of research methods in professional and technical communication:

- Engage in customer discovery research. Write a proposal for an entrepreneurial idea.

To earn a B in this course, you need to

- Turn in all but three assignments on time.

To earn a C in this course, you need to

- Complete all but five assignments on time.

To get the most from the course, I encourage you to assume an agentive mindset. Be the author. Be yourself. Find your voice. This doesn’t mean you cannot use AI, such as Chat GPT. But what it does mean is that you shouldn’t use an AI tool to do your writing for you. Remember, writing is thinking and at this point in time the AI tools aren’t capable of deep thought. If you use an AI tool, dialogue with it. Use it as a tool to help you think through the topics you’re exploring. And read its results carefully. Check sources. At this point of time, it’s a pathological liar.

Canvas Workaround

Nearly all assignments in Canvas will be marked as “Complete” or “Incomplete.” If Canvas shows you a percentage in your “Grades” view, ignore it. Any cumulative percentage that Canvas might show you is meaningless.

- You earn a score of complete on an assignment by completing it as described in the assignment description and rubric, course videos, and other supplementary materials, and (if available) as demonstrated by exemplars.

- You earn an incomplete by failing to submit an assignment, by submitting an assignment that does not fulfill the requirements, or by submitting an assignment that cannot be opened/read.

Late & Incomplete Assignments

Due dates. The due dates for all assignments are indicated in Canvas and in the schedule below. If you’re outside of Florida, make sure that you keep track of “Tampa Time” (EDT), as all due dates are listed according to the time zone in which the main campus is located. Most assignments are due on Monday. Take note of the following differences:

- 11:59 AM = 1 minute before noon. You probably won’t see this in our class.

- 11:59 PM or 23:59 = 1 minute before midnight. You’ll see this listed as a common assignment due-date time at Canvas.

Late assignments are those that are turned in after the due date listed in Canvas. You will not receive feedback on late work. After an assignment closes, you can no longer submit it.

Incomplete assignments are those that are not submitted, those that are submitted in an inappropriate form (for example, via email or incorrect file type) or a file that cannot be reviewed (this includes files that cannot be opened), or those that do not meet assignment guidelines or baseline criteria for passing. Incomplete assignments earn a score of “incomplete.”

No late assignments are not accepted. The only exceptions to this policy are students with USF-excused absences (medical absences require a doctor’s note; school activities such as USF teams require a note from Athletics BEFORE THE ABSENCE). You are welcome to work ahead if your schedule requires that.

Schedule

Week 1, 01/08 to 01/14 – Introduction to Professional & Technical Communication

“Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life.” – Marcus Aurelius

The goal of this exercise is for you to visually summarize the representation of PTC competencies .

- Read

- Based on your reading of the 4 assigned readings, create an information visualization (in .pdf format) that identifies the scope of competencies a professional writer needs to do well in the PTC discipline. Your information visualization should provide the attributions for the sources you quoted, summarized, or paraphrased from. At the bottom of the visualization, you should provide the references you quoted from, summarized, or paraphrased. Use APA 7.

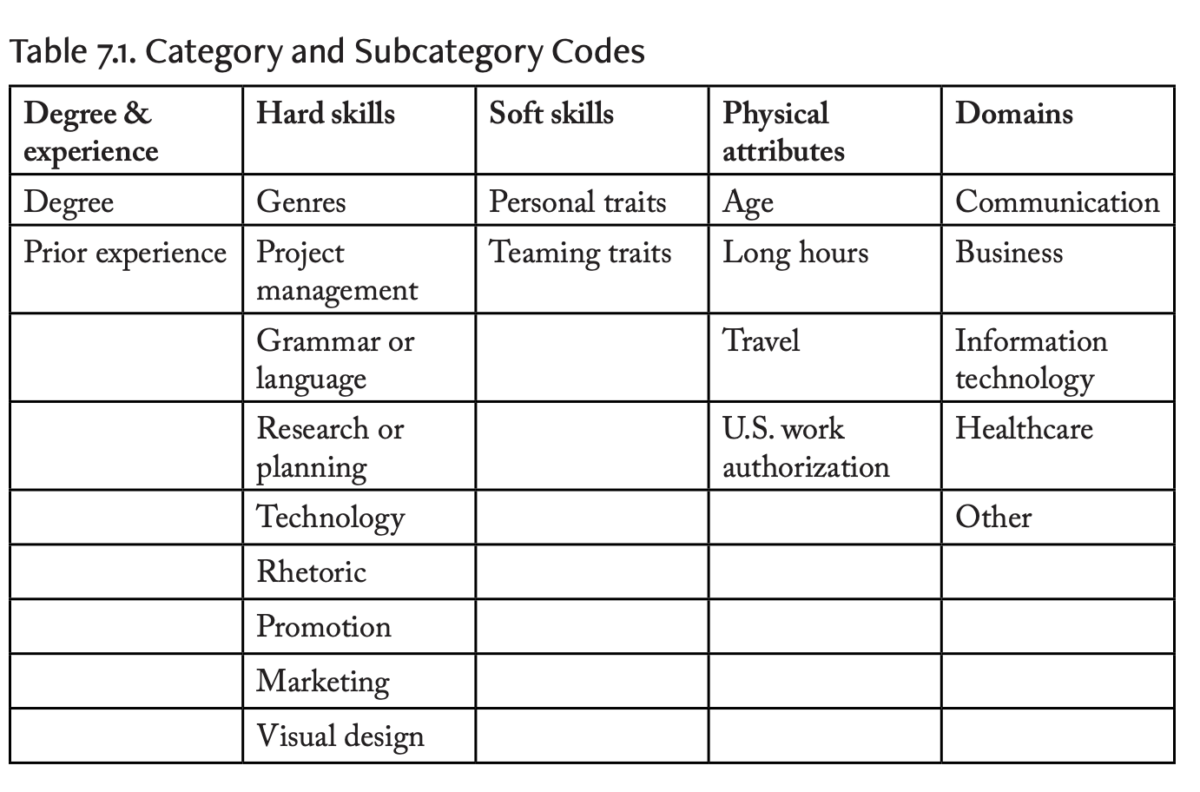

- Assessment: You will earn an incomplete if you merely copy a table from someone else’s table, such as Table 7.1 below from “7. Entry-Level.” Your information visualization should reflect a synthesis of information across the assigned readings.

- Submission Instructions: Upload a url or attach a .pdf to Canvas for grading.

Wednesday, 01/10, Assignment Due – What is PTC (Professional & Technical Communication) Competencies?

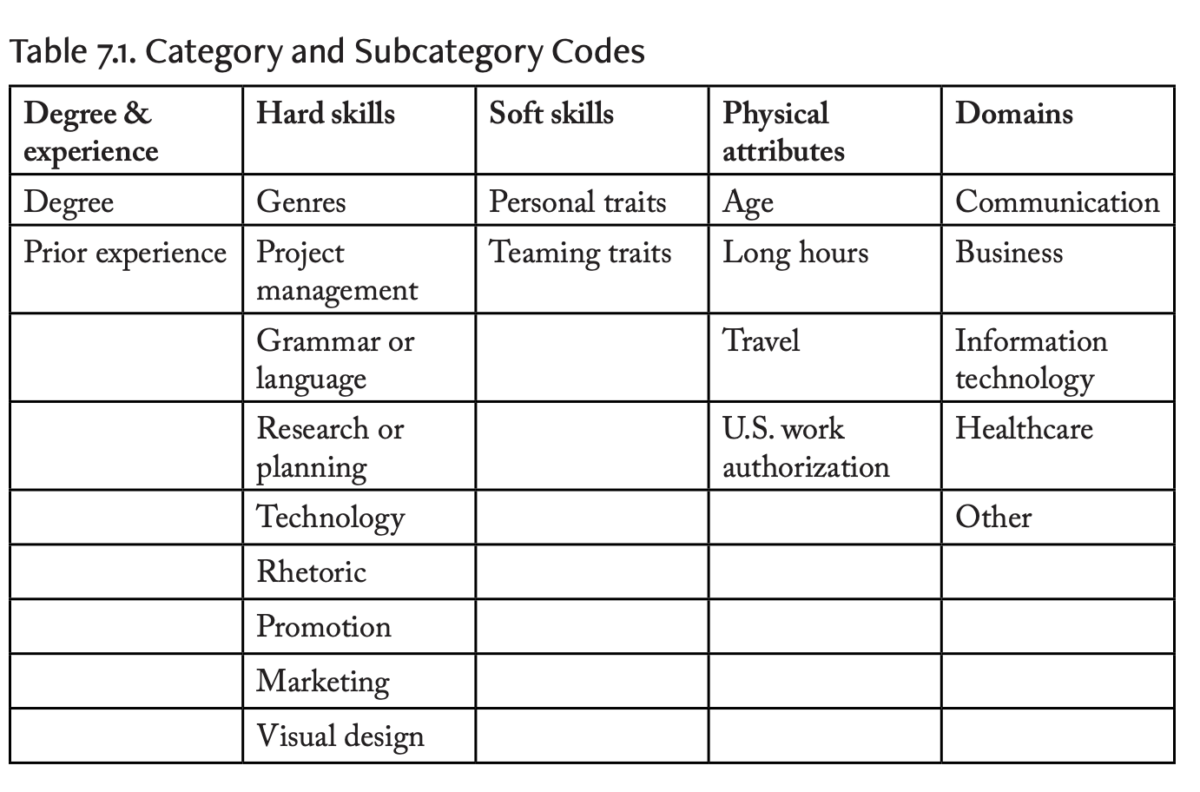

Source: “7. Entry-Level Professional Communicators in the Workplace: What Job Ads Tell Us.”

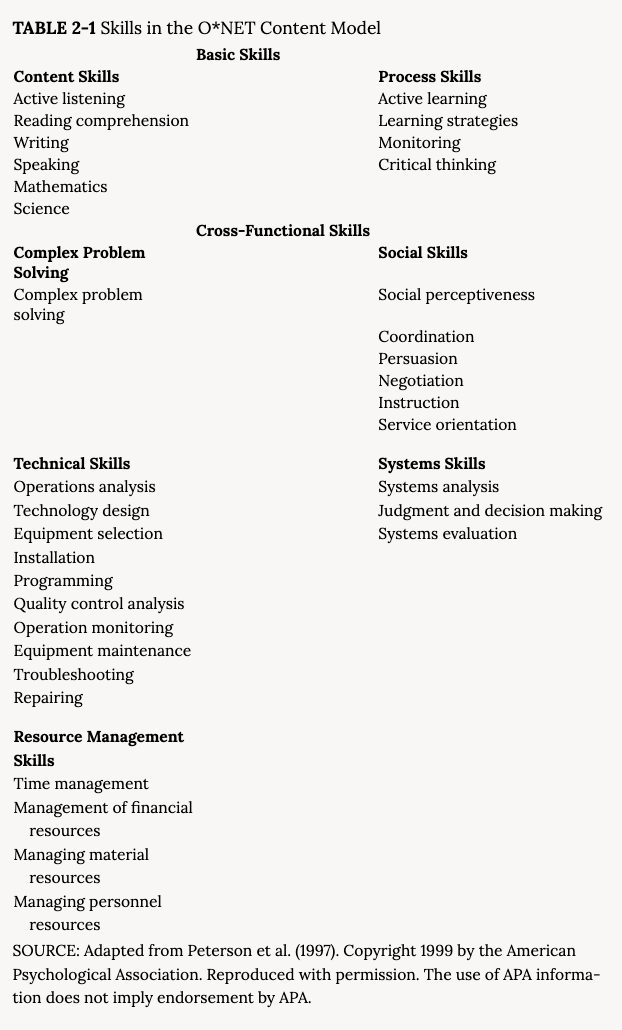

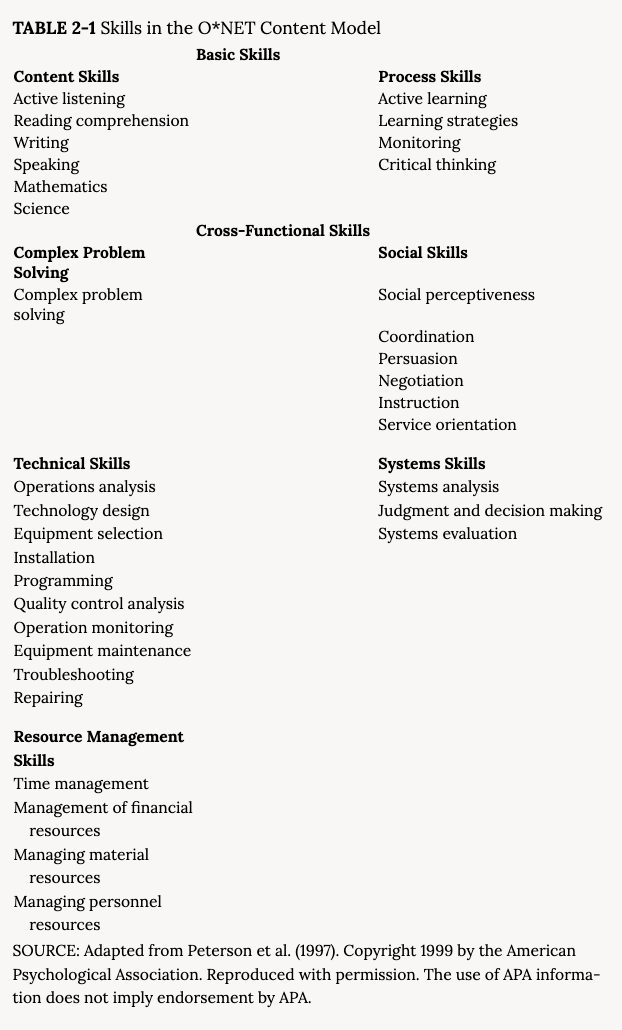

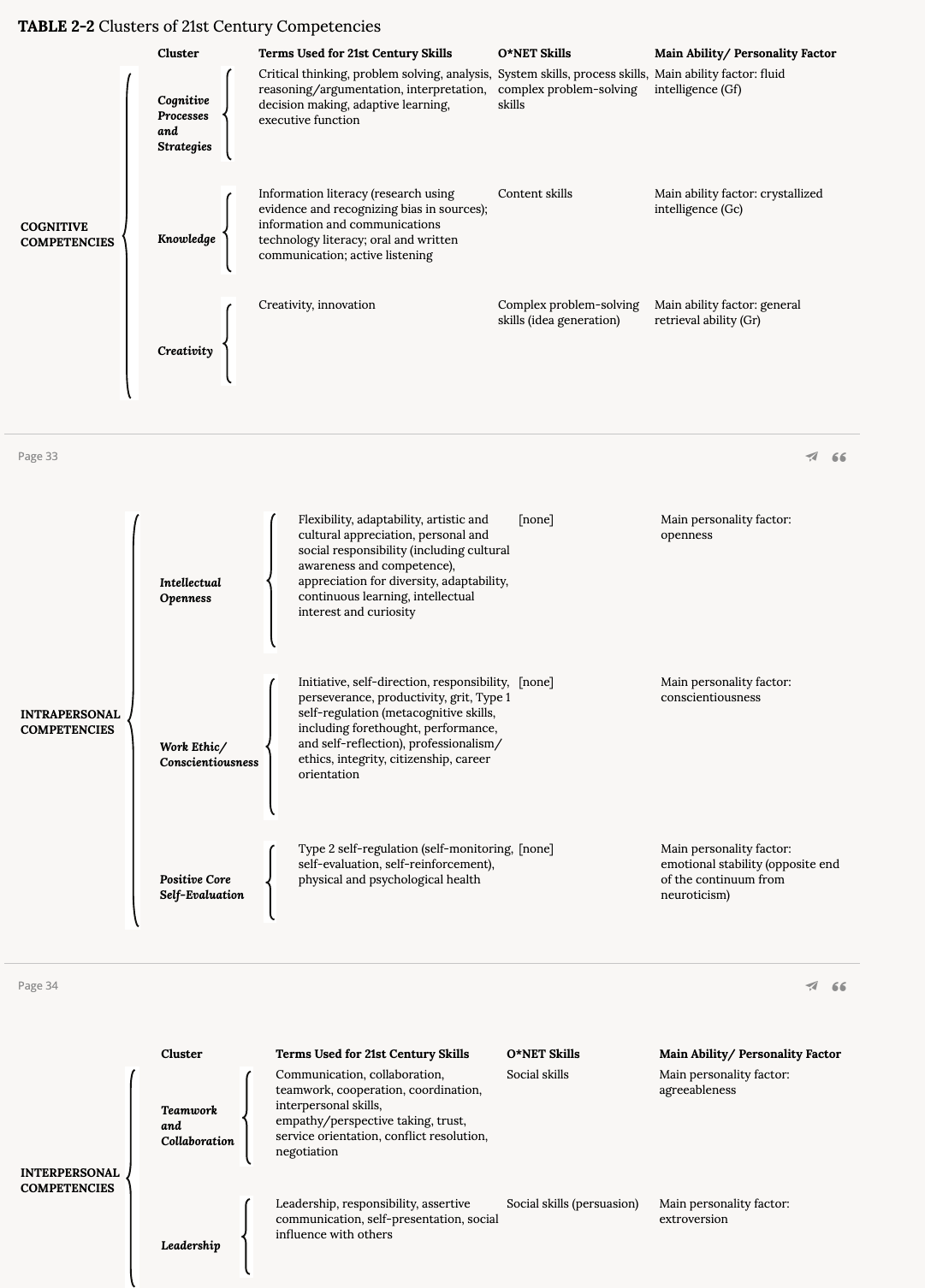

Source Education for Life and Work p 31

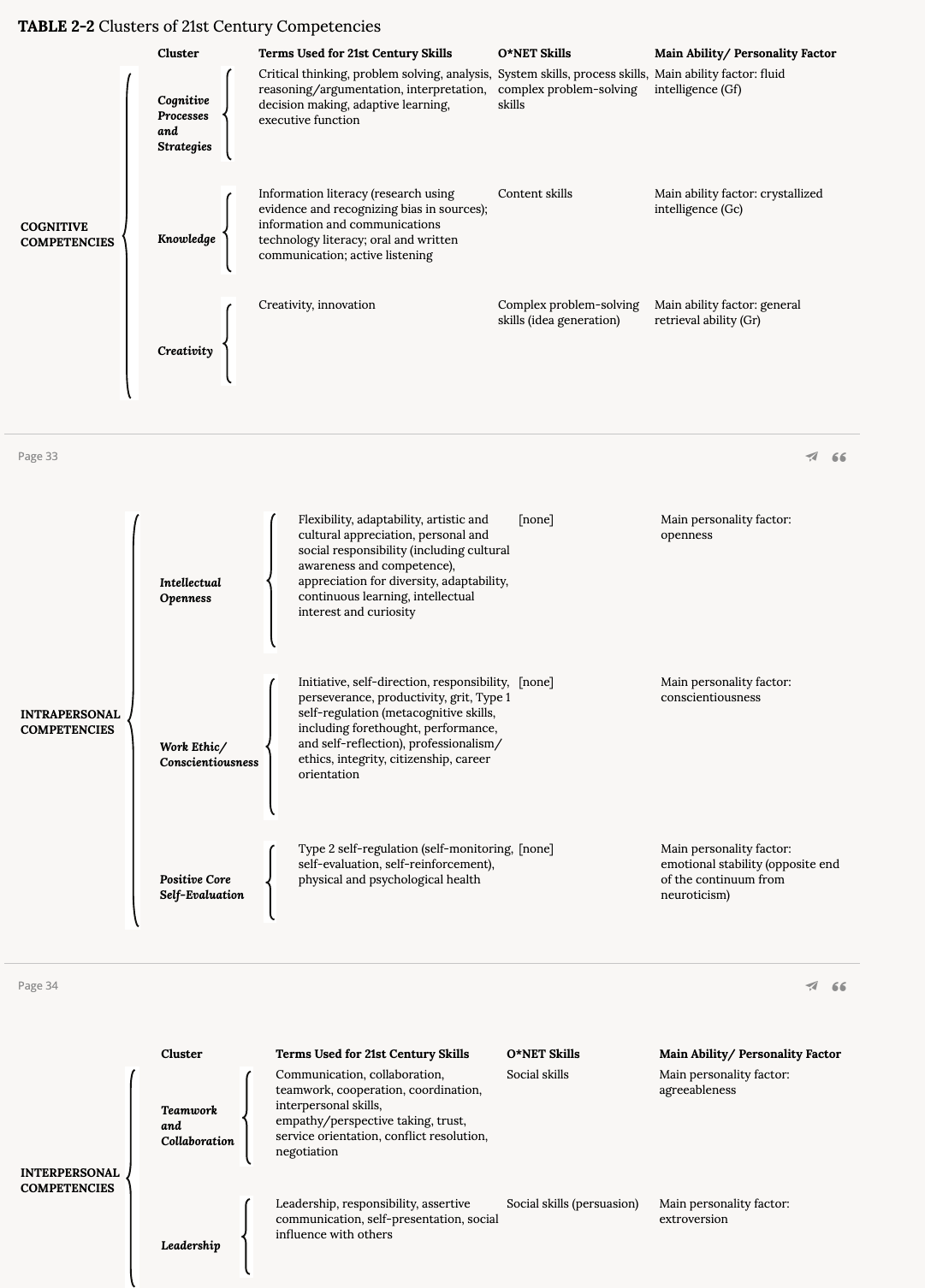

Source: Education for Life and Work

Assignment Guidelines

The goal of this exercise is for you to visually summarize information from a source.

- Read

- Deliverables:

- Develop an information visualization that visualizes research and/or theory on contract grading. Your visualization could address the challenges and limitations of contract grading. Or, it could illustrate the benefits researchers have found with contract grading.

- Length: 1 page

- Citation: APA 7

- Write a research summary: Summarize in your own words the story you aimed to communicate in your information visualization.

- Develop an information visualization that visualizes research and/or theory on contract grading. Your visualization could address the challenges and limitations of contract grading. Or, it could illustrate the benefits researchers have found with contract grading.

- Submission Instructions: Upload a copy of your research summary and visualization in .pdf. You may also upload a url where I can access your visualization online.

Week 2, 1/15 to 01/21 – Introduction to Research Methods

The goal of this exercise is for you to analyze the research methods used by DasBender, Gita, et al. (2023) in a research study published in a peer-reviewed, academic journal: writing studies:

DasBender, Gita, et al. (2023). Contract Grading and the Development of an Efficacious Writerly Habitus. Journal of Writing Assessment, 16(1). DOI: 10.5070/W4jwa.231

Wednesday, 1/17, Assignment Due – Summary of Research

- Review as needed:

- Read

- Engage in Critique of “Contract Grading” from a methodological perspective

- Analyze the knowledge community this peer-reviewed, academic article invokes: practitioners, researchers, and theorists in writing studies – the academic field that studies writing, rhetoric, and composition.

- What can you tell about the values of this community based on the way the publishers of The Journal of Writing Assessment acknowledge their use of use peer-review, present DOIs for articles, and publish with a CC-BY 4.0 Creative Commons copyright? Notice their statement regarding equal coauthorship and commitment to open-access information. How does that inform your sense of ethos? How do members of this discourse community use diction and jargon?

- Write a summary of research methods employed by DasBender et al.

- Skip the Review of Literature and jump down to the Study Overview & Rationale. Evaluate the authority of the article by analyzing the research methods DasBender et al. used to investigate the efficacy of labor-based grading practices. Notice DasBender et al. report on the following data collection and data analysis methods:

- IRB and Ethical Matters independent variables

- Labor-Based Contract

- Unilateral Grading Contracts (assessment includes evaluations of quality)

- Different types of FYC sections

- Racial/ethnic and sex/genderself identifidations

- status as multilingual or first-generation-in-college

- investigators excluded data from sections for which there weren’t comparisons (labor-based or unilateral contracts.

- Data Analyzed:

- course grades

- numerical survey responses

- narrative summary responses

- Skip the Review of Literature and jump down to the Study Overview & Rationale. Evaluate the authority of the article by analyzing the research methods DasBender et al. used to investigate the efficacy of labor-based grading practices. Notice DasBender et al. report on the following data collection and data analysis methods:

- Analyze the knowledge community this peer-reviewed, academic article invokes: practitioners, researchers, and theorists in writing studies – the academic field that studies writing, rhetoric, and composition.

- Deliverables

- Research Methods Summary: Write a summary of the research design DasBender et al report on in their research study on “Contract Grading.” Length: 250 to 500 words. Provide the detail your readers need to understand and to replicate the study. Use APA 7, as necessary.

- In a research summary, your readers expect you to

- provide the bibliographical information readers need to find the source. Cite “Contract Grading” in APA 7 format at the top of your document.

- categorize the research as primarily a contribution to scholarship — typically textual, hermeneutical methods — or as a contribution to empirical knowledge – or what they might positivistic knowledge or scientific knowledge

- In a research summary, your readers expect you to

- Research Methods Summary: Write a summary of the research design DasBender et al report on in their research study on “Contract Grading.” Length: 250 to 500 words. Provide the detail your readers need to understand and to replicate the study. Use APA 7, as necessary.

- Submission Instructions: Upload your summary to Canvas.

Sunday, 1/14, Assignment Due – Reflection on Research Article:

Contract Grading and the Development of an Efficacious Writerly HabitusSunday, 1/21, Assignment Due — Summary of Workplace Competencies in PTC

- Read “Writer Identity, Literacy, and Collaboration: 20 Technical Communication Leaders in 2020,” Rewriting Work

- Analyze the literature review and methods employed in “Writer Identity,”

- For this assignment, imagine you work for Sean Herring, Editor of the Recent & Relevant at Technical Communication.

- Herring has asked you to summarize the competencies graduates of PTC programs need to be competitive in the marketplace in 2025. He’s asked for you to use a memo format for your analysis, and to quote, summarize, paraphrase, and cite, as necessary. Your analysis should reflect an awareness of scholarly conversations on AI and the future of writing and work. Given its recency, Herring expects you to summarize the findings of “Writer Identity.” What are sociotechnological literacies? How is collaboration evolving in the workplace? What about the use of software tools for project development, such as Notion or Slack.

- Goal: don’t say the obvious. Be interesting, but also honest. Feel free to use a table or data visualization.

- Feel free to use bullets. If you do so, make sure they are parallel in structure.

- Submission Instructions: Upload to Canvas discussion board. Use this naming convention: Your Last Name – 2024 PTC Competencies,

Week 3, 01/22 to 01/28 – Research as a Conversation

Wednesday, 1/24, Assignment Due – Identification of Research Foci & Gaps

- Read

- Writing – Interesting Conversations or Gaps in PTC

- Skim through the table of contents of articles published by at least two journals in the PTC field over a one-year period (see list below, as developed and annotated by Jason Tham). Try to find two journals that are interesting to you. Skim the table of contents published by each edition of the publicationIdentify topics, research questions, and research methods used by the authors of these articles. What sorts of research questions does the journal/discipline seem to be preoccupied with, as suggested by the journals you reviewed? Can you identify enduring research concerns practitioners continue to explore? What “gaps” or interesting “research questions” occur to you? Don’t go over the obvious. Be interesting.

- Write about some of the conversations going on in professional writing that you find interesting. Try to identify one or two ideas for research.

- Submission: Discussion Forum Post

Jason Tham’s List of Journals in PTC

Journal of Business and Technical Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Theory driven; seems to balance qualitative and quantitative research

- Focus: Technical and business communication practices and pedagogy; discussions about training students to be professionals; some useful teaching strategies and cases

- Notes: Currently one of the top journals in technical communication; arguably most cited; has a strong tie to Iowa State’s professional communication program

Journal of Technical Writing and Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Slightly less theoretical than JBTC and TCQ but still heavy academic-speak

- Focus: Trends and approaches in technical communication practices and research

- Notes: One of the oldest technical communication journals in the US

Technical Communication (Society for Technical Communication)

- Nature: Arguably more practical than JTWC, JBTC, TCQ, and IEEE Transactions; caters to STC’s professional audience… and it’s associated with the STC’s annual summit

- Focus: Emerging topics, methods, and practices in technical communication; content management, information architecture, and usability research

- Notes: It’s behind a paywall some university libraries may not even access; there is an online version of the journal called Technical Communication Online… but it’s not as prominent as the print journal; seems to have a strong association with Texas Tech’s technical communication program

Technical Communication Quarterly (Association for Teachers of Technical Writing) (Taylor & Francis)

- Nature: Theoretical + pedagogical

- Focus: Teaching methods and exemplary approaches to research; features many exemplary qualitative research cases

- Notes: Another top journal in technical communication; produces many award-winning pieces; associated with ATTW so it has a huge academic following… especially those who also attend the annual Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC)

IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication (Institute of Electrical & Electronics Engineers – Professional Communication Society)

- Nature: 50-50 theory and practice

- Focus: Engineering communication as professional communication; empirical research

- Notes: Another old journal that has a lot of history; seems to have a strong tie to the University of North Texas’s technical communication department

IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society (IEEE Society on Social Implications of Technology)

- Nature: 30% technical, 70% philosophical discussions about social technologies

- Focus: Computers science, CS education, technical design, social computing

- Notes: Good for interdisciplinary work, digital humanities, and digital education

Communication Design Quarterly (Association for Computing Machinery – Special Interest Group on Design of Communication)

- Nature: Theoretical, methodological

- Focus: Offers many accessible (comprehensible) research reports on design methods, research practices, teaching approaches, and industry trends

- Notes: Open access…yay! Recently pursued an “online first” model where articles are published on a rolling basis; it’s considered the second-tier journal in the academic circle but it’s surely becoming more popular among technical communication scholars

Journal of Usability Studies (User Experience Professionals Association)

- Nature: For academics, this is highly practical

- Focus: Empirical research; mostly quantitative

- Notes: Independent journal not associated with an academic institution

Behaviour and Information Technology (Taylor & Francis)

- Nature: Computer science emphasis… so, experimental + theoretical

- Focus: Human-computer interaction; information design, behavioral science

- Notes: This is a UK journal… provides a nice juxtaposition to US journals and perspectives

Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (SAGE)

- Nature: Similar to BIT, experimental and theoretical

- Focus: Puts emphasis on the human factors and ergonomics discipline; draws from psychology

- Notes: As shown in its name… it’s a journal for the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society

Ergonomics in Design: The Quarterly of Human Factors Applications (SAGE)

- Nature: Slightly more theoretical than Human Factors

- Focus: Theoretical discussions, experiments, and demonstrations

- Notes: Also an HFES journal

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies (Elsevier)

- Nature: Theoretical

- Focus: More interdisciplinary than EID and Human Factors

- Notes: May be one that technical communication researchers feel more comfortable publishing in even if they are not working directly in HCI or computer science fields

Human Technology (Independent journal)

- Nature: Theoretical, philosophical

- Focus: Discusses technological futures and human-computer interaction

- Notes: It’s got less prestige compared to EID and Human Factors

Human Communication & Technology (Independent journal)

- Nature: Theoretical, empirical

- Focus: Communication studies and social technologies

- Notes: It’s fairly new and doesn’t seem to publish multiple issues a year

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (International Communication Association) (Oxford)

- Nature: Empirical; qualitative; quantitative

- Focus: Social scientific approach to computer-based communication; media studies and politics; social media research

- Notes: Top journal for solid communication technologies research

International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development (IGI Global)

- Nature: Empirical; qualitative; quantitative; practical

- Focus: Social scientific approach to technology studies and professional communication; seems catered to practitioner audience

- Notes: Has an interdisciplinary feel to it; one or two special issues are of specific interest to technical communication design

Business and Professional Communication Quarterly (SAGE)

- Nature: Theoretical, pedagogical

- Focus: Workplace communication studies and teaching cases

- Notes: A journal of the Association for Business Communication (ABC); top tiered for business writing and communication research

International Journal of Business Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Practical, pedagogical, experimental

- Focus: Similar focus to BPCQ

- Notes: Also an ABC journal (I am not sure why there is this other journal)

Programmatic Perspectives (Council for Programs in Technical and Scientific Communication)

- Nature: Programmatic, pedagogical

- Focus: Program and curriculum design; teaching issues; professional development of teachers

- Notes: Smaller journal… not sure how big is the readership but it’s got a good reputation

Xchanges: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Technical Communication, Rhetoric, and Writing across the Curriculum (Independent journal)

- Nature: Pedagogical, beginner research, experimental, teaching cases

- Focus: Technical communication, writing studies, rhet/comp, and everything in between!

- Notes: Open access journal with pretty good editorial support; provides mentorship to undergrad and graduate writing; multimedia friendly

RhetTech Undergraduate Journal (Independent journal)

- Nature: Beginner research, undergraduate research

- Focus: Writing studies, rhet/comp, technical communication

- Notes: Open access; print based (PDF) so not very multimedia-friendly

Sunday, 1/28, Assignment – Rhetorical Analysis of Genres Used in PTC

- Read, from Writing Commons:

- Genre Analysis

- Discourse Conventions

- Rhetorical Analysis

- Rhetorical Moves in Academic Writing

- Discourse Analysis

- Skim through two additional journals in PTC. Analyze the article publications over the past two years in these journals. Identify the titles, major sections, use of references. What research questions or other purposes inform these studies? Note shared discourse conventions, such as a deductive structure, a clear statement of the research question or hypothesis, an abstract, a review of literature (identification of the problem), and other common rhetorical moves. Note discourse conventions, methodological conventions, and genre conventions of research studies in the PTC discipline. For example, is the literature review synthesized into the statement of the problem, research question, or hypothesis?

- Submission Instructions: Write a memo to your peers and instructor. Share with your peers the insights you have gleaned by analyzing PTC journals about the research questions, research methods, and rhetorical moves of professional and technical writers? How do professional writers use visuals, such as tables and graphs, to exemplify methods and results? What sorts of evidence do they provide to provide support for claims? What common rhetorical moves and genres do the articles exemplify? What major sections do they include in their report Try to avoid restating the obvious. Be interesting. Remember, you are writing to your peers and they are already familiar with the study. To write well in this situation, you may play with visual design and data visualizations.

Week 4, 1/29 to 2/4 – Analysis of the Ideologies and Epistemologies That Inform Research Methods

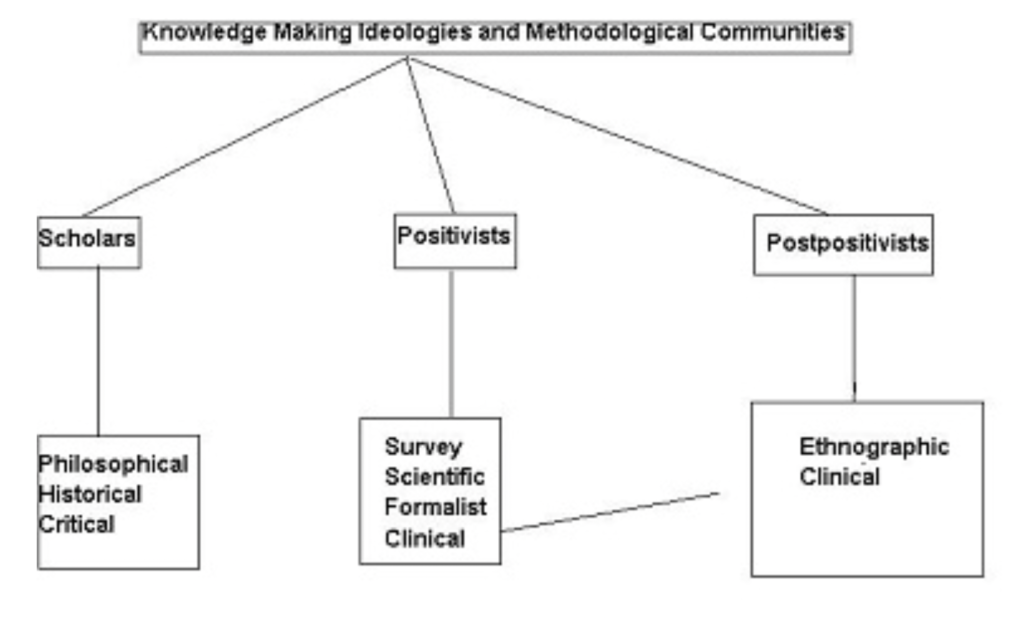

The goal this week is to consider how different research communities develop unique methods and distinctive ideas about how to conduct research.

What are Research Communities?

Research communities are groups of scholars, researchers, and practitioners who share a common set of epistemological assumptions, methodological approaches, and theoretical frameworks in their pursuit of knowledge. Different epistemological assumptions and ongoing evolutions in communication technologies gives rise to research communities – paradigms, which in turn shape the formation and evolution of research communities. This week we will consider ways epistemological positions impinge on interpretation and the writing process, particularly research methods..

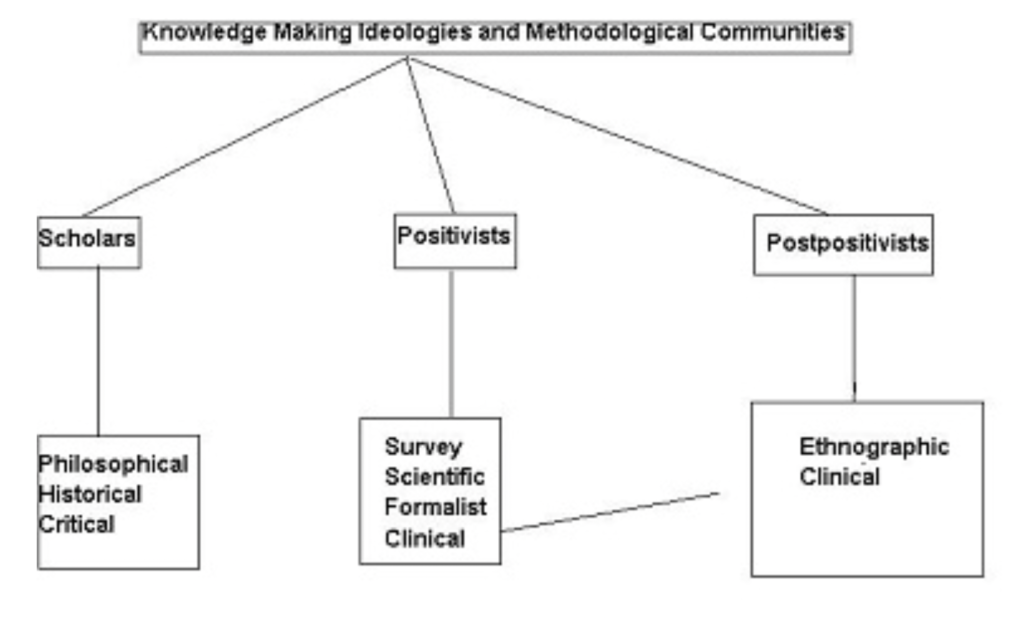

Source Moxley 2003 Wednesday, 1/31, Assignment Due – Research Summary

- Read, from Writing Commons:

- Write a Research Summary

- Refer to Jason Tham’s list of peer-reviewed journals in PTC.

- Identify a research study on a topic of interest to you.

- For your peers and others interested in the PTC discipline, summarize the study’s contribution to ongoing, research-based conversations. Identify the research community the study is addressing. You can do this by checking who publishes the journal (a university press? an association? an LLC?) Also, check the References. What journals, studies, or books is commonly cited? What form of citation do they use? Go to Google Scholar and check the citation count for the study’s authors. Check out their web pages to see if they are legit.

- What is the study’s unique contribution? How do the authors signal their unique contribution is to original scholarship?

- Do the authors engage in empirical research methods or scholarly research methods or a combination of both? Do they employ a “RAD” methodology — replicable, aggregable, data-supported method? What are the strengths and weaknesses of the study’s methods?

- Did you come across any ethical concerns? Did you notice any instances — such as when the investigators were interpreting results — that they made claims that we’re supported by their research methods?

- Submission Instructions: Upload your summary to the Canvas discussion board. At the top of your summary, provide the bibliographical information your readers need to find the study.

Sunday, 2/4, Optional Assignment Due – Document Planner for Your Independent Writing Project

If you wish to engage in the labor necessary to earn an A grade in this course, you need to complete one of the major assignments outlined above. To help you get started, I ask that you upload something that assures me you’ve selected a topic and are engaged in strategic research,. For instance you could upload an outline, a draft of your introduction, or artifacts related to the work you wish to conduct. The goal here is to identify a gap in the literature and identify a research question, that is worth asking. Here, as well, understand and embrace the inevitability of learning: investigators typically refine their research questions as they dig deeper into an archive and better understand the canon and scholarly discussions associated with a problem.

Read

- The Writing Process – Research on Composing

- Prewriting

- Planning Technical & Professional Documents

- The 7 Habits of Mind & The Writing Process

- The Secret, Hidden Writing Process: How to Tap Your Creative Potential

- The Ultimate Blueprint: A Research-Driven Deep Dive into The 13 Steps of the Writing Process

Submission Instructions

- Upload a link to your writing log and writer’s journal to Canvas — upload them as a .pdf attachment. Let me know which option you’ve chosen to engage in the necessary labor to earn an A grade. I’m curious about what progress you’ve made thus far. Let me know your questions, as well. How can I help you with your research?

Week 5, 02/05 to 02/11 – Research Ethics

Wednesday, 2/7, Assignment Due — Ethical & Methodological Critique

- Read

- Write a brief analysis of a published, peer reviewed research study’s methods from an ethical or methodological perspective.

- Share with your peers and instructor the bibliographical information they need in APA 7 to find the study you’re reviewing. Hyperlink to it if possible. Write an analysis of a peer-reviewed article on a topic of your choice, published during the past 3 years, that uses primary research methods (either qualitative or quantitative). Try to find a study that uses research methods that you find especially interesting. Analyze whether the authors followed or failed to follow ethical research methods. In your opinion, is the study authoritative? Beyond methods or methodology, you may also analyze the investigators’ use of textual research. When they introduced secondary research to position their study in relation to other ongoing scholarly conversations, did they establish the credibility of the sources and information? Did they accurately reflect the research, theories, and events they summarized? Did their tone seem objective and balanced? Did they note counterarguments? Did they explain the methods of the studies they cited to illustrate the authority of those works? Did they mention if their work was IRB approved? Did they make claims that were unsupported by the evidence?

Sunday, 2/11, Assignment Due – Write a Research Summary of an Interesting, Peer-Reviewed study

- Engage in strategic searching on a topic of interest to you. Look for a peer-reviewed study that employs a methodological approach that interests you. Look for ethnographies, case studies, interviews.

- Write a 250 word research summary for your peers and instructor. Your summary should report on an interesting peer-reviewed research study. Introduce the study by providing the bibliographical info in APA 7 at top of page. Establish the authority of the journal it was published in. Outline the study’s research methods. Explicate any ethical or methodological concerns you have

- Submission Instructions: Upload the summary in .pdf format to Canvas. Or, provide a url where it can be accessed.

Week 6, 02/12 to 02/18

Wednesday, 2/14, Optional Assignment Due

Instructions

This is an optional project. Only those students who are engaging in the labor for an A grade need to complete this project. For this assignment, your audience is me — your instructor. I want to make sure you’re engaging in some work on your optional project. Complete these 3 deliverables:

- Research Protocol

- If you are putting in the labor for an A grade, then update me on your major project. If you plan to engage in some empirical research, you must complete a Research Protocol.

- Annotated Bibliography. If you are authoring your texts based on textual research, you must complete an annotated bibliography of three or 4 sources. I’m eager to hear about your strategic searching plans. I encourage you to explore the University’s databases. As a student at USF, you have access to the gated web: the global archive of peer-reviewed research.

- Project Management Status

In a sentence or two, summarize what you’ve done thus far. Then provide examples. For instance, you could provide drafts and screenshots of work conducted. You could provide a draft of your introduction, a literature review. You could present a schedule for completing major chunks of the project you’ve selected. Clarify your research methods and efforts to ensure ethical, professional standards. - Submission: Upload .pdf file to Canvas

Sunday, 2/18, Assignment Due – Rhetorical Analysis & Research Summary of an Interesting PTC Study or Method

- Engage in rhetorical analysis of an interesting, peer-reviewed research study published in an authoritative journal, website, professional organization, or distinguished publishing house

- Write a summary of a peer-reviewed research study that in your opinion uses interesting research methods or questionable research interpretations/results. This study must be published in a credible journal. It needs to be peer reviewed. In your assignment, at the top of page, provide the bibliographical information for the study using APA 7. Underneath the citation, provide word count for the summary. Write for a reader who hasn’t read the study. Introduce the title, authors, purpose/research question, and research methods. Be sure to vet sources and to clarify their authority when you introduce them in your prose. Then focus on explaining the methods the investigator(s) used to address their research question.

- Submission Instructions: Upload to Canvas Discussion Board

Week 7, 2/19 to 02/25 – Introduction to Corpus Linguistics

Wednesday, 2/21, Assignment Due

For this and the next few assignments, we will be using this gdoc as our corpus: “Syllabi Policies for AI Generative Tools.” Compiled by Lance Eaton, an instructional designer, “Syllabi Policies” is a repository of instructors’ AI policy statements on their syllabi. Eaton has also made the resource available as a google spreadsheet.

- Read

- Pull some data from Syllabi Policies and then use that data to experiment with your data file and a corpus tool, such as

- Random Questions:

- Is there a way to plot author’s institution on a global map?

- Could you plot the 10 most commonly used words or phrases in this corpus?

- How frequent are the words we’d expect to see, such as plagiarism, academic dishonesty, ethics, student code of conduct?

- Submission Instructions: This assignment has two deliverables:

- Upload a memo that explains to me and your peers which corpus tool you experimented with and what aspect of the corpus you analyzed.

- Upload a .pdf of an illustration of your findings. Or, you may provide a url that links out to your data visualization. Or you may provide screenshots of your findings.

Week 8, 02/26 to 03/03 – No Assignments Are Due This Week

Dear Students,

Please note that I will be unavailable this week.

I understand playing around with a new tool or idea takes time. I personally feel that sometimes as a writer I need to retreat from society and the chatter of small talk. Thus, I’m giving you this week to take some time to

- Experiment with multiple corpus tools, such as

- Check out Zotero and develop a References list in APA 7. While there’s an initial learning curve, having a free tool like this during your schoolwork can be a huge time saver.

- If you are putting the labor in to earn an A in this course, engage in the strategic searching necessary to become conversant on the scholarly conversation, the topic, that interests you.

Week 9, 3/4 to 3/10

Welcome back. I hope last week was productive for you.

Note: Spring Midterm Grading Ends

Wednesday, 3/6, Assignment Due – 2nd Effort at Corpus Analysis or Rhetorical Analysis

This assignment offers you a second opportunity to

- work with corpus linguistic tools to interpret and describe some aspect of the “Syllabi Policies” corpus

- engage in textual analysis of the corpus that you find most interesting. For instance, you could pull from the corpus any comments about a concept such as attribution, plagiarism, composing, intellectual property, or ethical behavior to better understand how they professors define and use these concepts in their grading.

Recommended Readings

Invention Questions

Below are some sample lines of analysis you might pursue to develop a detailed, honest description of professor’s reaction to the emergence of AI in higher education. For this assignment, you cannot possibly address all of these questions. Thus, it’s strategic to choose one or two of these questions to analyze for this assignment.

- How can we discern the demographics of the contributors to “Syllabi Policies?”

- Do faculty who work in similar institutions — private universities, state universities, R1 universities, liberal arts colleges — share any perspectives? Or, can professors’ comments be sorted by discipline or subject to reveal any interesting results?

- By reviewing the course title, can you ascertain whether faculty from particular disciplines (e.g., the sciences, social sciences, humanities) tend to share perspectives?

- Are there any points a majority of faculty agree on?

- For instance do faculty agree “You may not use GenAI to produce an assignment in its entirety” (Noël – Boston College)

- What percentage of the faculty are entirely opposed to AI in the classroom?

- What percentage of the faculty explicitly said any use of AI is an instance of plagiarism and academic dishonesty?

- What percentage of faculty support the use of AI with an attribution on the part of the writer?

- How do professors ask students to attribute their use of AI? Do they provide specific citation conventions? For instance, do any of them point to the APA guidelines for citing AI? Are faculty concrete or vague about the policies they expect students to follow in the classroom?

- How do faculty describe the usefulness of AI during various stages of the writing process — prewriting, inventing, drafting, collaborating, researching, planning, organizing, designing, rereading, revising, editing, or proofreading.

- What percentage of faculty support the use of AI without any attribution?

- What penalties will students pay if they use AI and it has hallucinated — it has created false academic journals or publishing companies?

- What happens to students if they have cited work that is “fake” or offensive?

- How many of the authors explicitly mention academic integrity and ethics?

How To Cite from the Corpus

- Get the Author Name from the Contributor field

- Provide Name of Course as if it’s the title

- List the Name of the Institution as the Publisher

Submission Guidelines:

- Explain the corpus linguistics analysis or rhetorical analysis you conducted. Succinctly summarize what you learned about the professors’ perceptions regarding the potential and threat AI poses to higher education.

Friday, 3/8, Optional Assignment Due

- For those of you who are engaging in the labor to earn an A in this course, provide a progress report. Show me a copy of what you’ve completed thus far. Tell me what you need to do next. Make a Ghent chart to illustrate the work you need to complete in order to submit the assignment on time.

Week 10, 03/11 to 03/17 – Spring Break Week

Week 11, 03/18 to 03/24

Context – Call to Write2

This week, as we return from spring break, I ask that we endeavor as a group, 22 to 25 people, to coauthor a document, titled “AI Policy for College-Level Writing Courses – Guide to Students.

2Here, I acknowledge that having so many people coauthoring one document will be chaotic. For this exercise, though, I ask that you play the believing game. Focus on thepositive: Please view this as an experiment in invention, collaboration, and peer production. For our collaborative work on this project, I ask that you spend at least two hours on each exercise.

Audience

We are writing to the higher education community. Many schools, such as USF, have not yet to publish policy statements on AI. There is currently broad interest in a helpful guide to students that explains AI classroom policies from an evidence-based perspective.

Context/Purpose

- The goal of our research is to

- Consider the workplace competencies professionals need in order to be competitive in the PTC marketplace

- Identify the range of AI Policies used by faculty throughout the U.S. at a range of institutions (high school, college, etc.)

- Recommend AI Policies for Students and Professors in Higher Education

Voice & Prose Style

Adopt a professional writing prose style.

Wednesday, 3/20, Assignment Due – Adding Bios & Contributing as an Author

- Under Authors, list your last name in alphabetical order (with semicolons separating authors). Provide a link to your bio page at gDocs. For this page, you can share a version of it that is “view” only.

- Under at least one section at “AI Policy“, make a contribution as an author. For example, if you think your early work on corpus linguistic analysis is worth sharing — if it gives an interesting and credible account for how professors experienced AI in higher education last year — please share it. Add your results to the results section and add your methods to the. methods section.

- In Canvas upload a note to me that explains your contribution to the group project. Feel free to share screenshots but probably safest to upload your document in .pdf.

Sunday, 3/24, Assignment Due – Interview-1

- Read

- Working With People, Try This

- Writer Identity, Literacy, and Collaboration: 20 Technical Communication Leaders in 2020

- Interview a professor, a student, or a business person on the impact of AI on academic and professional writing.

- Write, using gdocs, a summary of the interviewers’ thoughts on the role of AI in higher education

- Submission Instructions:

- Add under the “Interviews” heading at “AI Policy” a link to your interview. Please use the following convention to name your interviews:

- YourLastName-Title-of-Your-Interview

- Add under the “Interviews” heading at “AI Policy” a link to your interview. Please use the following convention to name your interviews:

Week 12, 3/25 to 03/31

Note: Spring last day to withdraw; no refund & no academic penalty.

Wednesday, 3/27, Assignment Due – Interview-2

- Engage in a second interview

- Write summary

- Submit to Canvas in .pdf format

Sunday, 03/31, Assignment Due

- Read

- Survey Research

- Work with peers in the class to develop a useful survey to be administered to students and professors to ascertain their experiences last year with AI in their assignments, homework, and quizzes.

- Or — as an alternative to working on the survey project — continue your efforts at textual or empirical research.

- Upload to Canvas a url where I can go to access the survey.

Week 13, 4/01 to 4/07

Wednesday, 4/03, Optional Assignment Due – Project Update #4

- For those of you who are engaging in the labor to earn an A in this course, provide me with a progress report. Show me a copy of what you’ve completed thus far. Tell me what you need to do next. Make a Ghent chart to illustrate the work you need to complete in order to submit the assignment on time.

Sunday, 4/07, Assignment Due – Launch the Survey

- Following review by me and your peers, launch the survey.

- Continue ongoing research, including other empirical methods (interviews or ethnographies) and scholarly methods (e.g., searching Social Media on AI Policies)

- Work at Coauthoring “AI Policy”

- Write a note to me that updates me on your efforts to coauthor “AI Policy”

Week 14, 4/08 to 4/14

Wednesday, 4/10, Assignment Due – Update on Contributions to “AI Policy“

- At “AI Policy,” begin working on Recommended AI Policies for Faculty and Recommended AI Guidelines for Students. For now, don’t delete anyone’s ideas. Let’s just list and develop recommendations and guidelines as they come to us.

- Through Canvas write to me an update regarding your efforts to coauthor “AI Policy.” Let me know if you have any questions.

Sunday, 4/14, Assignment Due – Recommended AI Policies and Guidelines for Students

- Summarize the survey results and, as applicable, work the survey results into the “AI Policy” document.

- At “AI Policy,” begin revising and editing.

- Use the Elements of Style as a critical, stylistic lens to work toward concision, simplicity, clarity, and unity.

- Upload to Canvas a more refined Recommended AI Policies and Guidelines for Students.

Week 15, 04/15 to 04/21

Wednesday, 04/17, Assignment Due – Reflection Memo

- Write a reflection memo to me that outlines what you’ve learned about research methods as a result of this introduction. I’m curious to hear your ideas for improving the course.

Nothing is Due. At USF, Test Free week is 4/20 to 4/26

Week 16, 04/22 to 04/24

4/22 – Last Day of Class

- Optional Project is due for those of you engaging in the labor necessary to warrant an A grade.

. I make weekly and often biweeklyAnnouncements. For instance, for the class I may clarify a student question, or I may give some group feedback on an assignment. Please email me when you have questions. I’ll typically respond back in 24 hours. If you don’t hear from me within 24 hours, pleases send me a 2nd email. If I’m online when your message comes in, I’ll jump on a quick call with you, via Zoom, Teams, or Google Meet. We can schedule longer meetings, as necessary.

I’m all for your using AI tools such as Chat GPT or Midjourney. I think moving forward, like it or not, we will be working a lot with AI to accelerate communication processes. However, I strongly encourage you to develop your own unique style, voice — and thoughts. At this point of time, it’s easy to recognize a prose style generated by AI: it tends to address content at the superficial level, it hallucinates, and it tends to follow a formulaic sentence and organizational structure. Remember, as well, that tools such as ChatGPT are founded on the greatest intellectual property theft of all time: The developers vacuumed the internet, swallowing all of that content whole. They didn’t care about U.S. copyright law or intellectual property rights — or the laws that protect a writer’s work in other countries. Instead, they dumped all of those words into a bucket — what corpus linguists call a corpus. Then they used statistical probability analysis to predict which letter or letters are likely to follow other letters. Then they used humans to train the dataset.

You should know that I can tell when work is based on AI and served up whole as if context doesn’t matter in clear communication. I can also determine, I believe, whether your prose has been worked though multiple iterations. Eventually, it may be impossible to discern AI prose from human prose. Presently, though, that’s not the case.

Currently, in higher education there is a great deal of conversation and debate about how professions and disciplines should respond to the usage of AI assisted writing for classroom assignments.

In my opinion, we are in a pickle: the conventions that have guided our society regarding intellectual property are shifting in response to the emergence of large language models. Professional organizations, journals, and book publishers are working on new methods for attributing sources generated from AI. Lawyers and businesses and the government are wresting with how AI can be used for the benefit of humanity. We are at a revolutionary moment when it comes to language practices. People in school and workplaces are suddenly grappling with what is an acceptable usage of AI and how authors should cite their usage of AI when composing.

In both academic and professional writing,Meanwhile, it is important to note that in school settings and work settings it is a violation of academic integrity for you to submit work that has make up sources and evidence. Thus, if you experiment with AI, you must not simply “copy and paste.” Instead, you need to check every source and quotation — really every word.

So that I may refer to you with the appropriate pronoun in Canvas, the University’s course LMS (learning management system), please set your preferences for your personal pronoun at Canvas > Settings. If you have a first name change request for Canvas, please email IDM-Help@usf.edu from your official USF email account. You do not need to provide personal details for the request. Tell USF the first name you want to show in Canvas. This will also change your name in the directory, but it will not change your email address.

Best wishes for a productive semester.

Professor Moxley

Course Outcomes

- Learn about the research methods employed by practitioners in PTC

- Question ways ideology and epistemology impinges on both interpretation and research methods

- Sharpen your information literacy perspectives and practices

- Learn how to manage research projects.

- Learn about the genres of discourse used by professional writers, especially those engaged in customer discovery research

- Learn to adopt a professional writing style.

Course Delivery

This course is offered asynchronously by USF, which means it does not require real-time interactions either in person or online. Rather than convening at a specific time, this format allows you the flexibility to engage with course materials and complete assignments according to your own schedule. Below, you will find a detailed outline of the course assignments along with a schedule designed to guide you through these tasks in a timely and structured manner.

Required Course Tools – Writing Spaces

- Canvas (for grading purposes & Announcements)

- Each week, I will use Announcements @ Canvas to adjust the schedule, if necessary, clarify student questions, and give group feedback. I will ask you to upload some assignments to Canvas discussion forms and drop boxes.

- gDocs

- Zotero (for citations — unless you have another favorite app for citation management)

Required Texts

- GCF Global. Google Drive and Docs

This is a thorough, free guide to using gDocs. You’ll need this resource if you are unsure how to create and share gDocs - Web Accessibility Initiative. Images Tutorial

This is a free resource. Not sure how to caption images? Learn how to make your images more accessible. - Rewriting Work

- Syllabi Policies for AI Work

- We will study this corpus for our collaborative, class-wide project. Note this form is also available as a searchable spreadsheet

- Try This

This is the major course textbook for this course - Writing Commons

You can block the ads by adding Adblock Plus, a free Chrome extension. The ad blocker works great.

Grading

Your grade will be based on your labor over the semester. This approach is called “labor-based contract grading.” Ideally, contract grading frees you up to try new things because you won’t be penalized for taking risks. In fact, I strongly (!!) encourage you to try new things and push yourself. Growth and strength result from struggle and working through confusion.

Grading Criteria

To earn a C in this course, you need to

- Complete the Major Project – a Research Study. Topic is open.

- Default Topic: Research the effects of AI in Professional and Technical Communication

- Turn in all but five assignments on time.

To earn a B in this course, you need to

- Complete the Major Project – a Research Study. Topic is open.

- Default Topic: Research the effects of AI in Professional and Technical Communication

- Turn in all but three assignments on time.

Hopefully, this reassures you that if you work through the assignments, the lowest grade you’ll receive is a B – so long as you do the assignments. To get the most from the course, I encourage you to assume an agentive mindset. Be the author. Be yourself. Find your voice. This doesn’t mean you cannot use AI, such as Chat GPT. But what it does mean is that you shouldn’t use an AI tool to do your writing for you. Remember, writing is thinking and at this point in time the AI tools aren’t capable of deep thought. If you use an AI tool, dialogue with it. Use it as a tool to help you think through the topics you’re exploring. And read its results carefully. Check sources. At this point of time, it’s a pathological liar.

To earn an A in this course, you need to meet all of the requirements outlined above to earn a B grade AND you must work on a second project for this class that is being completed solely for this class. Choose from one of the following options. Or, if you have a better idea, tell me about it. I’d like for you to write a topic that you find interesting.

- Write in any nonfiction genre or media the equivalent of a 1000 to 1500 word article on any topic of your choice. This text should be written for a specific discourse community/magazine/journal. Even if at heart its an alphabetical text, it needs to be well designed. For instance, it should have a professional page design, use visual rhetoric, and include data visualizations such as infographics

- Develop a blog for a public audience. Spend the semester blogging and researching how to commercialize a blog. Research the topic you’d like to write about and the market niche. Identify leading blogs in that market. Each week write at least two 500 word posts on topics for your market/audience. Add necessary visualizations (at least one for each post).

- In the course plan below, you are scheduled to summarize and critique about five articles published in the PTC field. For this project, you would continue that work but do more of it. You’d read and summarize/critique two additional articles each week from the list of PTC articles below.

- Write a 500-word book review of a book that explores research methods in professional and technical communication. Choose from the following recently published OER books or email me if you wish to write a book review for an alternative book related to the topic of research methods in professional and technical communication:

- Engage in customer discovery research. Write a proposal for an entrepreneurial idea.

Canvas Workaround

Nearly all assignments in Canvas will be marked as “Complete” or “Incomplete.” If Canvas shows you a percentage in your “Grades” view, ignore it. Any cumulative percentage that Canvas might show you is meaningless.

- You earn a score of complete on an assignment by completing it as described in the assignment description and rubric, course videos, and other supplementary materials, and (if available) as demonstrated by exemplars.

- You earn an incomplete by failing to submit an assignment, by submitting an assignment that does not fulfill the requirements, or by submitting an assignment that cannot be opened/read.

Late & Incomplete Assignments

Due dates. The due dates for all assignments are indicated in Canvas and in the schedule below. If you’re outside of Florida, make sure that you keep track of “Tampa Time” (EDT), as all due dates are listed according to the time zone in which the main campus is located. Most assignments are due on Monday. Take note of the following differences:

- 11:59 AM = 1 minute before noon. You probably won’t see this in our class.

- 11:59 PM or 23:59 = 1 minute before midnight. You’ll see this listed as a common assignment due-date time at Canvas.

Late assignments are those that are turned in after the due date listed in Canvas. You will not receive feedback on late work. After an assignment closes, you can no longer submit it.

Incomplete assignments are those that are not submitted, those that are submitted in an inappropriate form (for example, via email or incorrect file type) or a file that cannot be reviewed (this includes files that cannot be opened), or those that do not meet assignment guidelines or baseline criteria for passing. Incomplete assignments earn a score of “incomplete.”

No late assignments are not accepted. The only exceptions to this policy are students with USF-excused absences (medical absences require a doctor’s note; school activities such as USF teams require a note from Athletics BEFORE THE ABSENCE). You are welcome to work ahead if your schedule requires that.

Workflow

Workflow refers to the pace and order of the assignment you’ll complete. I’ve structured assignments and due dates to help you make consistent progress, and all assignments relate in a synergistic fashion. I dislike “busy work,” and I assume that you do, too, so I’ve streamlined the class as much as possible. All of the little assignments you complete help you tackle the major assignments.

When I assign something it’s because I believe that completing the assignment will help you be more successful in the class and with writing more generally. So one of the big things I’m asking of you is to undertake the work I assign with an open mind and with an attitude that allows you to embrace the work.

Please trust me and trust the process. I always have your success in mind. Your well-being and your growth as a writer are high on my list of priorities.

Schedule

Week 1, 01/08 to 01/14 – Introduction to Professional & Technical Communication

“Nothing has such power to broaden the mind as the ability to investigate systematically and truly all that comes under thy observation in life.” – Marcus Aurelius

Wednesday, 01/10, Assignment Due – What is PTC (Professional & Technical Communication) Competencies?

- Read

- Based on your reading of the 4 assigned readings, create a table or information visualization (in .pdf format) that identifies the scope of competencies a professional writer needs to do well in the PTC discipline.

- Submission Instructions: Upload the table to the Canvas discussion board. If necessary, see GCF Global. Google Drive and Docs to learn to work with tables in gdocs

Source: “7. Entry-Level Professional Communicators in the Workplace: What Job Ads Tell Us.”

Source Education for Life and Work p 31

Source: Education for Life and Work

Sunday, 01/14, Assignment Due – Reflection on Contract Grading

- Read

- Review, as needed

- Deliverables:

- Using a table or some other visual format, create a rubric for contact grading that you believe could work well in this this class. To construct the rubric, please consider the course goals and objectives. Also consider the earlier work you completed regarding workplace competencies. Consider ways to help students master these competencies and ways to assess them

- Length: No more than 2 pages.

- Examples: Contract Grading Rubric – Labor Emphasis

- Write a summary to me that explains your rubric design.

- Using a table or some other visual format, create a rubric for contact grading that you believe could work well in this this class. To construct the rubric, please consider the course goals and objectives. Also consider the earlier work you completed regarding workplace competencies. Consider ways to help students master these competencies and ways to assess them

- Submission Instructions: Upload your table/information visualization to the course Discussion Board. Upload it as a .pdf, if possible.

Week 2, 01/15 to 01/21 – Introduction to Research Methods

Wednesday, 01/17, Assignment Due

- Read – Ptc

- Chapter 1. What are Research Methods?, Try This

- Discourse Community, Epistemology, Research, Research Methodology, and Research Methods, Writing Commons

- Analyze the literature review and appeals to authority. “Contract Grading and the Development of an Efficacious Writerly Habitus“

- Write a critique and reflection on the research methods employed in “Contract Grading”

- In 200 to 250 words or less, summarize the research methods employed by Gita DasBender, Nate Mickelson, and Leahn Souffrant in “Contract Grading.” Explain how they used primary and secondary research methods to inform their investigation. Address any critiques or questions you have about their research methods. Don’t belabor the obvious. Yet hit the important matters: What was their research question? Who was the audience for the work? Scientists? Scholars (Philosophers, Historians)? Practitioners? What methods were used? Empirical Methods? Quantitative Methods? Qualitative Methods? Ethnographic Methods? Case Study Methods? Did you notice any ethical concerns? Quote, summarize, paraphrase, and cite, as necessary.

- Submission: Canvas Discussion Board

Sunday, 01/21, Assignment Due — Summary of Workplace Competencies in PTC

- Read “Writer Identity, Literacy, and Collaboration: 20 Technical Communication Leaders in 2020,” Rewriting Work

- Analyze the literature review and methods employed in “Writer Identity,”

- For this assignment, imagine you work for Sean Herring, Editor of the Recent & Relevant at Technical Communication. Herring has asked you to summarize the competencies graduates of PTC programs need to be competitive in the marketplace in 2025. He’s asked for you to use a memo format for your analysis, and to quote, summarize, paraphrase, and cite, as necessary. Your analysis should reflect an awareness of scholarly conversations on the future of work. Given its recency, Herring expects you to summarize the findings of “Writer Identity.” What are sociotechnological literacies? How is collaboration evolving in the workplace? What about the use of software tools for project development, such as Notion or Slack. Goal: don’t say the obvious. Be interesting, but also honest. Feel free to use a table or data visualization.

- Submission Instructions: Upload to Canvas discussion board. Use this naming convention: Your Last Name – 2024 PTC Competencies,

Week 3, 01/22 to 01/28 – Research as a Conversation

Wednesday, 01/24, Assignment Due – Identification of Research Foci & Gaps

- Read

- Writing – Interesting Conversations or Gaps in PTC

- Skim through the table of contents of articles published by at least two journals in the PTC field over a one-year period (see list below, as developed and annotated by Jason Tham). Skim the table of contents published by each edtion of the publicationIdentify topics, research questions, and research methods used by the authors of these articles. What sorts of research questions does the journal/discipline seem to be preoccupied with, as suggested by the journals you reviewed? Can you identify enduring research concerns practitioners continue to explore? What “gaps” or interesting “research questions” occur to you? Don’t go over the obvious. Be interesting.

- Submission: Discussion Forum Post

Jason Tham’s List of Journals in PTC

Journal of Business and Technical Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Theory driven; seems to balance qualitative and quantitative research

- Focus: Technical and business communication practices and pedagogy; discussions about training students to be professionals; some useful teaching strategies and cases

- Notes: Currently one of the top journals in technical communication; arguably most cited; has a strong tie to Iowa State’s professional communication program

Journal of Technical Writing and Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Slightly less theoretical than JBTC and TCQ but still heavy academic-speak

- Focus: Trends and approaches in technical communication practices and research

- Notes: One of the oldest technical communication journals in the US

Technical Communication (Society for Technical Communication)

- Nature: Arguably more practical than JTWC, JBTC, TCQ, and IEEE Transactions; caters to STC’s professional audience… and it’s associated with the STC’s annual summit

- Focus: Emerging topics, methods, and practices in technical communication; content management, information architecture, and usability research

- Notes: It’s behind a paywall some university libraries may not even access; there is an online version of the journal called Technical Communication Online… but it’s not as prominent as the print journal; seems to have a strong association with Texas Tech’s technical communication program

Technical Communication Quarterly (Association for Teachers of Technical Writing) (Taylor & Francis)

- Nature: Theoretical + pedagogical

- Focus: Teaching methods and exemplary approaches to research; features many exemplary qualitative research cases

- Notes: Another top journal in technical communication; produces many award-winning pieces; associated with ATTW so it has a huge academic following… especially those who also attend the annual Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC)

IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication (Institute of Electrical & Electronics Engineers – Professional Communication Society)

- Nature: 50-50 theory and practice

- Focus: Engineering communication as professional communication; empirical research

- Notes: Another old journal that has a lot of history; seems to have a strong tie to the University of North Texas’s technical communication department

IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society (IEEE Society on Social Implications of Technology)

- Nature: 30% technical, 70% philosophical discussions about social technologies

- Focus: Computers science, CS education, technical design, social computing

- Notes: Good for interdisciplinary work, digital humanities, and digital education

Communication Design Quarterly (Association for Computing Machinery – Special Interest Group on Design of Communication)

- Nature: Theoretical, methodological

- Focus: Offers many accessible (comprehensible) research reports on design methods, research practices, teaching approaches, and industry trends

- Notes: Open access…yay! Recently pursued an “online first” model where articles are published on a rolling basis; it’s considered the second-tier journal in the academic circle but it’s surely becoming more popular among technical communication scholars

Journal of Usability Studies (User Experience Professionals Association)

- Nature: For academics, this is highly practical

- Focus: Empirical research; mostly quantitative

- Notes: Independent journal not associated with an academic institution

Behaviour and Information Technology (Taylor & Francis)

- Nature: Computer science emphasis… so, experimental + theoretical

- Focus: Human-computer interaction; information design, behavioral science

- Notes: This is a UK journal… provides a nice juxtaposition to US journals and perspectives

Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society (SAGE)

- Nature: Similar to BIT, experimental and theoretical

- Focus: Puts emphasis on the human factors and ergonomics discipline; draws from psychology

- Notes: As shown in its name… it’s a journal for the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society

Ergonomics in Design: The Quarterly of Human Factors Applications (SAGE)

- Nature: Slightly more theoretical than Human Factors

- Focus: Theoretical discussions, experiments, and demonstrations

- Notes: Also an HFES journal

International Journal of Human-Computer Studies (Elsevier)

- Nature: Theoretical

- Focus: More interdisciplinary than EID and Human Factors

- Notes: May be one that technical communication researchers feel more comfortable publishing in even if they are not working directly in HCI or computer science fields

Human Technology (Independent journal)

- Nature: Theoretical, philosophical

- Focus: Discusses technological futures and human-computer interaction

- Notes: It’s got less prestige compared to EID and Human Factors

Human Communication & Technology (Independent journal)

- Nature: Theoretical, empirical

- Focus: Communication studies and social technologies

- Notes: It’s fairly new and doesn’t seem to publish multiple issues a year

Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (International Communication Association) (Oxford)

- Nature: Empirical; qualitative; quantitative

- Focus: Social scientific approach to computer-based communication; media studies and politics; social media research

- Notes: Top journal for solid communication technologies research

International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development (IGI Global)

- Nature: Empirical; qualitative; quantitative; practical

- Focus: Social scientific approach to technology studies and professional communication; seems catered to practitioner audience

- Notes: Has an interdisciplinary feel to it; one or two special issues are of specific interest to technical communication design

Business and Professional Communication Quarterly (SAGE)

- Nature: Theoretical, pedagogical

- Focus: Workplace communication studies and teaching cases

- Notes: A journal of the Association for Business Communication (ABC); top tiered for business writing and communication research

International Journal of Business Communication (SAGE)

- Nature: Practical, pedagogical, experimental

- Focus: Similar focus to BPCQ

- Notes: Also an ABC journal (I am not sure why there is this other journal)

Programmatic Perspectives (Council for Programs in Technical and Scientific Communication)

- Nature: Programmatic, pedagogical

- Focus: Program and curriculum design; teaching issues; professional development of teachers

- Notes: Smaller journal… not sure how big is the readership but it’s got a good reputation

Xchanges: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Technical Communication, Rhetoric, and Writing across the Curriculum (Independent journal)

- Nature: Pedagogical, beginner research, experimental, teaching cases

- Focus: Technical communication, writing studies, rhet/comp, and everything in between!

- Notes: Open access journal with pretty good editorial support; provides mentorship to undergrad and graduate writing; multimedia friendly

RhetTech Undergraduate Journal (Independent journal)

- Nature: Beginner research, undergraduate research

- Focus: Writing studies, rhet/comp, technical communication

- Notes: Open access; print based (PDF) so not very multimedia-friendly