Synonymous Terms

Composing Process

In writing studies, the writing process may also be known as the composing process. This may be due to the dramatic influence of Janet Emig’s (1971) dissertation, The Composing Processes of Twelfth Graders. Emig’s research employed think-aloud protocols and case-study methods to explore the composing processes of high school students.

Creative Process

In creative writing and literature, the writing process may be known as the creative process.

In the arts and humanities the term creative process is reserved for artistic works, such as paintings, sculptures, performance art, films, and works of literature.

Related Concepts: Composition Studies; Creativity; Felt Sense; Growth Mindset; Habits of Mind; Intellectual Openness; Professionalism and Work Ethic; Resilience; Self Regulation & Metacognition

What is the Writing Process?

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project.

People experience and define the writing process differently, according to their historical period, literacy history, knowledge of writing tools, media, genres — and more.

One of the takeaways from research on composing is that we’ve learned writers develop their own idiosyncratic approaches to getting the work done. When it comes to how we all develop, research, and communicate information, we are all special snowflakes. For example,

- Hemingway was known for standing while he wrote at first light each morning.

- Truman Capote described himself as a “completely horizontal author.” He wrote lying down, in bed or on a couch, with a cigarette and coffee handy.

- Hunter S. Thompson wrote through the nights, mixing drinking and partying with composing

- J.K. Rowling tracked the plot lines for her Harry Potter novels in a data.

- Maya Angelou would lock herself away in a hotel room from 6:30 a.m. to 2 p.m. so she has no distractions.

| Recommended Exercise When you complete a project, take a moment to reflect on your composing processes. |

Research on composing processes conducted over the past 60 years has led to three major distinct ways of defining and conceptualizing the writing process:

- The writing process refers to a series of steps or strategies:

- prewriting, invention, research, collaboration, planning, designing, drafting, rereading, organizing, revising, editing, proofreading, and sharing or publishing

- The writing process refers to cognitive, problem-solving strategies

- The writing process refers to the act of making composing decisions based on nonrational factors such as embodied knowledge, felt sense, inner speech, and intuition.

1. The writing process refers to writing process steps

The writing process is often characterized as a series of steps or stages. During the elementary and middle-school years, teachers define the writing process simply as prewriting, drafting, revising, and editing. Later, in high-school and college, as writing assignments become more challenging, teachers introduce additional writing steps: invention, research, collaboration, designing, organizing, proofreading, and sharing or proofreading.

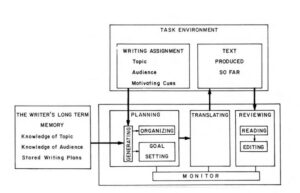

2. The writing process refers to Problem-Solving Strategies

As an alternative to imagining the writing process to be a series of steps or stages that writers work through in linear manner, Linda Flower and John Hayes suggested in 1977 that writing should be thought of as a “thinking problem,” a “problem-solving process,” a “cognitive problem solving process,” or a “goal-directed thinking process.”

3. The writing process refers to the act of making composing decisions based on flow, felt sense and other elements of embodied knowledge

For some writers, viewing the writing process as a series of steps or problems feels to mechanistic, impersonal and formulaic. Rather than view that the writing process to be a series of writing steps or problem solving strategies, Sondra Perl, an English professor, suggests that composing is largely a process of listening to one’s felt sense — one’s “bodily awareness of a situation or person or event:

“A felt sense doesn’t come to you in the form of thoughts or words or other separate units, but as a single (though often puzzling and very complex) bodily feeling”. (Gendlin 1981, 32-33)

FAQs

What are Writing Process Steps?

In elementary and middle schools in the U.S., the writing process is often simplified and presented at four or five key steps: prewriting, writing, revising, and editing–and sometimes and publishing or sharing. As students progress through school, the writing process is presented in increasingly complex ways. By high school, teachers present “the writing process steps” as

- Prewriting

- Invention

- Research

- Collaboration

- Planning

- Designing

- Drafting

- Rereading

- Organizing

- Revision

- Editing

- Proofreading

- Sharing – Publishing

Is there one perfect way to work with the writing process?

No, there is no one ideal writing process. The steps of the writing process a writer engages in vary from project to project. At times composing may be fairly simple. Some situations require little planning, research, revising or editing, such as

- a grocery list, a to-do list, a reflection on the day’s activity in a journal

- documents you routinely write, such as the professor’s letter of recommendation, a bosses’ performance appraisal, a ground-water engineer’s contamination report.

Over time, writers develop their own unique writing processes. Through trial and error, people can learn what works for them.

Composing may be especially challenging

- when you are unfamiliar with the topic, genre, medium, discourse community

- when the thesis/research question/topic is complicated yet needs to be explained simply

- when you are endeavoring to synthesize other’s ideas and research

- when you don’t have the time you need to perfect the document.

What are the main factors that effect how writers compose documents?

Writers adjust their writing process in response to

- the context

- Writers assess the importance of the exigency, the call to write, before commiting time and resources to launching

- the complexity of the topic or rhetorical situation

- the writers access to information

- their literary background

- What they know about the canon, genre, media and rhetorical reasoning

- their writerly background

- the audience

- the schedule.

Why Does the Writing Process Matter?

The writing processes that you use to compose documents play a significant role in determining whether your communications are successful. If you truncate your writing process, you are likely to run out of the time you need to write with clarity and authority.

- Studying the writing processes of successful writers can introduce you to new rhetorical moves, genres, and composing processes. Learning about the composing processes of experienced writers can help you learn how to adjust your rhetorical stance and your writing styles to best accomplish your purpose.

- By examining your writing processes and the writing processes of others, you can learn how to better manage your work and the work of other authors and teams.

- By recognizing that writing is a skill that can be developed through practice and effort, you can become more resilient and adaptable in your writing endeavors.

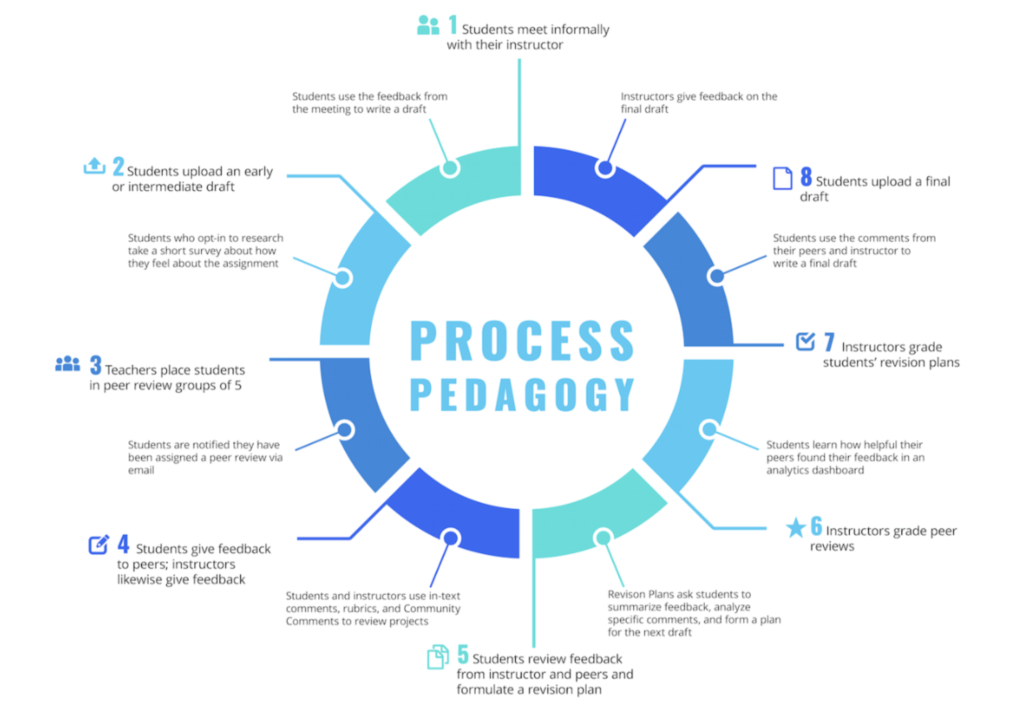

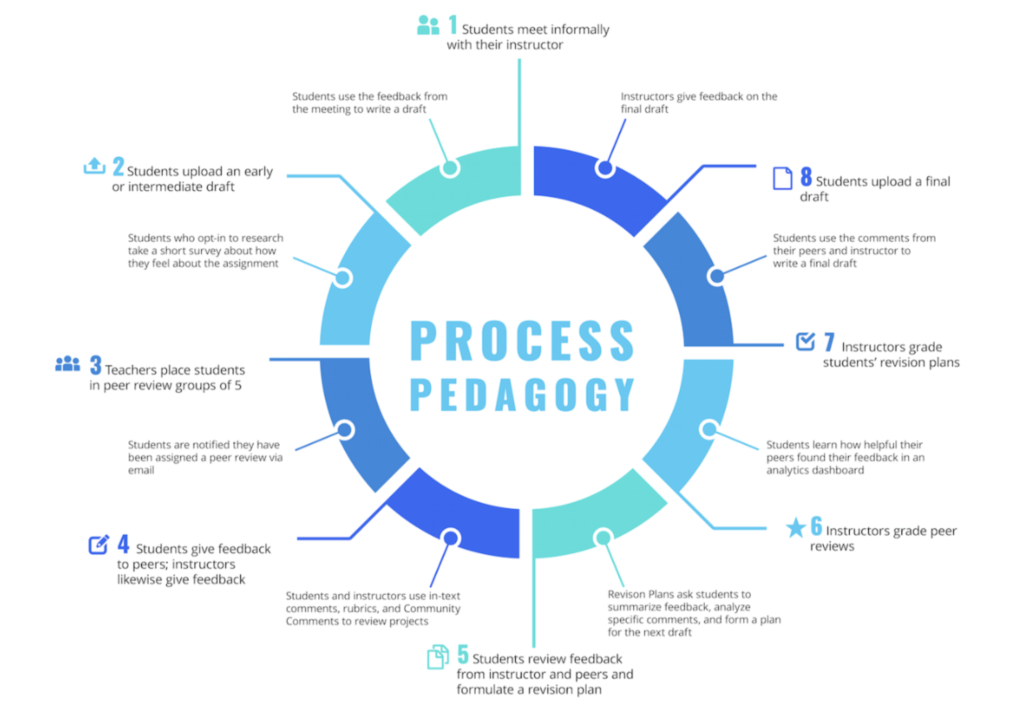

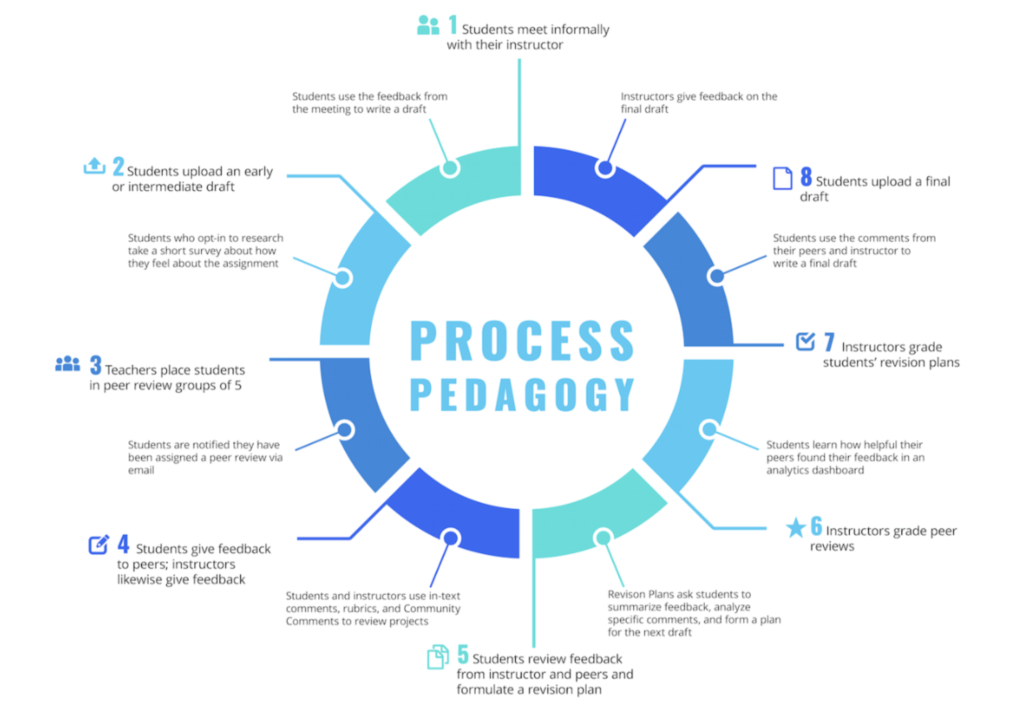

[ For an example of process pedagogy, see professional writing, which breaks the processes involved in writing a recommendation report down into a 15-week schedule. ]

Do experienced writers compose in different ways than inexperienced writers?

Yes. Experienced writers engage in more substantive, robust writing processes than less experienced writers.

- Experienced writers tend to have more rhetorical knowledge and a better understanding of composing steps and strategies than inexperienced writers.

- Experienced writers tend to be more willing than inexperienced writers to make substantive changes in a draft, often making changes that involve rethinking the meaning of a text. Some professional writers may revise a document hundreds of times before pushing send or publishing it.

- Experienced writers engage in revision as an act of internal conversation, a form of inner speech that they have with themselves and an imagined other–the internalized target audience. In contrast, inexperienced writers tend to confuse editing for revision. They tend to make only a few edits to their initial drafts, focusing primarily on surface-level changes such as correcting grammar, spelling, or punctuation errors.

- Experienced writers are adept at working collaboratively, leveraging the strengths of team members and effectively coordinating efforts to produce a cohesive final product. Inexperienced writers may struggle with collaboration, communication, and division of labor within a writing team

What is Process Pedagogy?

Process pedagogy, which is also known as the process movement, emerged in the United States during the late 1960s and early 1970s. In The Making of Knowledge in Composition, Steve North (1987) links the emergence of process pedagogy to

- Sputnik and America’s concern it was falling behind Russia

- the GI Bill and the changing demographics of undergraduate students in the post-war era.

Additionally, process pedagogy emerged in response to dissatisfaction with traditional, product-oriented approaches to teaching writing. In the current-traditional paradigm of writing, the focus of the classroom was on “the composed product rather than the composing process; the analysis of discourse into words, sentences, and paragraphs; the classification of discourse into description, narration, exposition, and argument; the strong concern with usage (syntax, spelling, punctuation) and with style (economy, clarity,

emphasis)” (Young, 1978, p. 25).

The process movement reflected a sea change on the part of middle schools, high schools, and universities in the U.S. Traditionally, classroom instruction focused on analysis and critique of the great works of literature:

“The student is (a) exposed to the formal descriptive categories of rhetoric (modes of argument –definition, cause and effect, etc. — and modes of discourse — description, persuasion, etc.), (b) offered good examples (usually professional ones) and bad examples (usually his/her own) and (c) encouraged to absorb the features of a socially approved style, with emphasis on grammar and usage. We help our students analyze the product, but we leave the process of writing up to inspiration” (Flower and Hayes, 1977, p. 449).

In contrast to putting the focus of class time on analyzing great literary works, the canon, process pedagogy calls for teachers to put the emphasis on the students’ writing:

- Emphasis on the writing process:

- Students need help with prewriting, invention, research, collaboration, writing, designing, revising, organizing, editing, proofreading, and sharing

- Fluency precedes correctness:

- Teachers do not comment on grammar and style matters in early drafts. Instead, they focus on global perspectives. They prioritize the flow of ideas and expression over correctness in grammar and mechanics.

- Discovery through writing:

- Students engage in prewriting and invention exercises to discover and develop new ideas

- Ongoing revision:

- Students repeatedly revise their works in response to self-critique, peer review, and critiques from teachers

- Teachers should provide constructive feedback throughout the writing process.

What does “teach the process and not the product mean”?

“Teach the process not the product” is both the title of a Donald Murray (1972) article and the mantra of the writing process movement, which emerged during the 1960s.

The mantra to teach the process not the product emerged in response to the research and scholarship conducted by Donald Murray, Janet Emig, Peter Elbow, Ann Berthoff, Nancy Sommers, Sondra Perl, John Hayes and Linda Flower.

What does it mean to describe the writing process as recursive?

The term recursive writing process simply means that writers jump around from one activity to another when composing. For instance, when first drafting a document, a writer may pause to reread something she wrote. That might trigger a new idea that shoots her back to Google Scholar or some other database suitable for strategic searching.

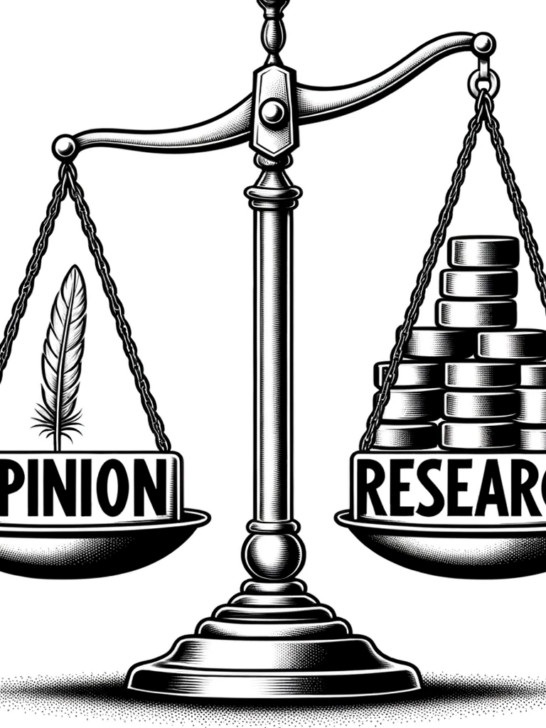

How do researchers study the writing process?

The writing process is a major subject of study of researchers and scholars in the fields of composition studies, communication, writing studies, and AI (artificial intelligence).

The writing process is something of a black box: investigators can see inputs (e.g., time on task) or outputs (e.g., written discourse), yet they cannot empirically observe the internal workings of the writer’s mind.

At the end of the day investigators have to jump from what they observe to making informed guesses about what is really going on in the writer. Even if investigators ask a writer to talk out loud about what they are thinking as they compose, the investigators can only hear what the writer is saying: they cannot see the internal machinations associated with the writer’s thoughts. If a writer goes mute, freezes, and just stares blankly at the computer screen, investigators cannot really know what’s going on. They can only speculate about how the brain functions.

Research Methods

To study or theorize about the writing process, investigators may use a variety of research methods.

| Informal Research Methods | Informal Research is a research method that gathers data/information/evidence anecdotally or based on convenience rather than in accordance with the systematic methods prescribed by methodological communities. |

| Mixed Research Methods | Mixed Research is a type of empirical research method that relies on both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection and analysis. |

| Textual Research Methods | Textual Research Methods are methods investigators use to interpret texts, to assess knowledge claims, and to develop new knowledge. |

| Empirical Research Methods | Empirical research is a research method that investigators use to test knowledge claims and develop new knowledge. Empirical Research may be called Primary Research, Positivistic Research, Scientific Research, or Field Research. Examples: Mixed Research Methods; Qualitative Research Methods; Quantitative Research Methods; Usability and User Experience Research |

| Quantitative Research Methods | Quantitative Research is a form of empirical research method that gathers and interprets numerical data (i.e., numbers and statistics) as opposed to qualitative data (i.e., words) in order to develop knowledge or test knowledge claims. |

| Qualitative Research Methods | Qualitative Research, an empirical method, focuses primarily on gathering and interpreting qualitative data (i.e., words and ideas) rather than numerical data (i.e., numbers and statistics) in order to test knowledge claims and develop knowledge |